by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Source: Deposit Photos

An intriguing description of how intuition works comes from Ingo Swann’s explanation of ESP. Swann, along with Stanford physicist Harold Puthoff, developed the process for remote viewing that the U.S. military used. Swann, a remote viewer himself, did the teaching. In his book, Everybody’s Guide to Natural ESP, Swann says anyone can do remote viewing. Essentially it involves nonconscious information rising to consciousness. Here’s the gist of how he thought it works.

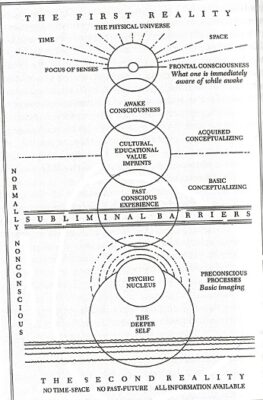

Subliminal Barrier Filters Information

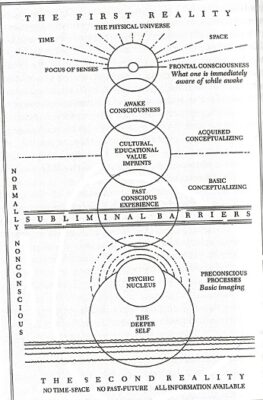

Our “deeper self,” our subconscious, transcendent self, soul, or any variety of names for it, is connected to the energetic quantum information world underlying the physical universe—the “second reality” notation at the base of the diagram below from Swann’s book. That’s where the intuitive information comes from. So that we’re not flooded and overwhelmed, Swann says a subliminal barrier allows only select information to make it to our conscious, waking mind. Without that barrier, it would be like listening to 1,000 radio channels simultaneously. Usually we receive the information that’s most important to us.

Like the quantum world itself, which physicists are still trying to understand, intuition works by its own logic and processes. Those are represented in the diagram by the overlapping circles in the nonconscious space below the subliminal barrier. The deeper self’s qualities must operate similar to those of quantum reality, which facilitates the connection. Neither intuition nor the quantum world seems to be affected by time, space or the resistance of matter.

What’s Going On Below the Mind’s Surface?

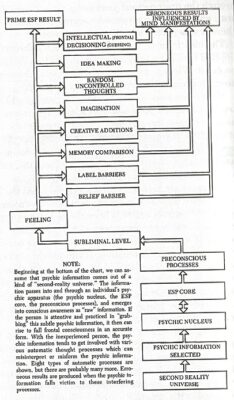

So, what’s going on below the subliminal barrier? What are those preconscious processes? It’s murky. Nonconscious stimuli enter idea and creativity generating processes that interact with memory to take on a form that can be recognized by logic and analysis when it reaches conscious awareness. This subjective process cannot be willfully controlled. With practice, it can be recognized though and conducive environments can be set up to facilitate it. Artists and other creative professionals often use rituals, a favorite place, or some personalized means to bring on the muse. Swann thought ESP uses the same channels and similar processes.

Unlocking Natural Talents & Learning Discernment

Focusing attention and training awakens our waking consciousness to the deeper self’s workings. Even so, the nonconscious information we access can be diverted or misinterpreted by conceptualizing filters on its way to full frontal consciousness (shown in the upper portion of the diagram).

That’s what training helps with. In his book about working as a remote viewer for the military, Lyn Buchanan says Swann’s method doesn’t “teach someone to be psychic.” It “teaches them to get rid of all those blocks that prevent them from using the natural and hidden talents they already have. For most people, that is a surprising amount.” (p. 32). Like any talent though, some people are more naturally able to access subliminal information and bring it accurately to consciousness than others.

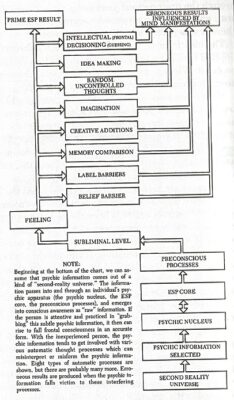

This diagram, also from Swann’s book, shows some of our basic and acquired conceptualizing filters that can keep our deeper self’s messages from getting to waking consciousness fully and accurately. The conscious mind uses these frameworks and strategies to process information. They may work well with information our normal sensory system brings in. But intuitive information is likely to be grasped whole; those sudden insights that don’t need interpretation. Their meaning is clear on arrival. If the info gets snared by these filters instead of reaching waking consciousness raw, it may come out partial or wrong. It’s possible though, if the conscious filters align with the intuitive content, the conscious message could be reasonably accurate.

For most of us, nonconscious information appears sporadically and spontaneously, often in bodily or emotional form or in dreams or daydreams. The sense that someone we love is in danger is a good example. We may not know the specifics, just the visceral sense or physical discomfort and who it’s associated with. How the deeper self initiates that spontaneous, non-conscious awareness that shoots directly to the surface remains a mystery, one even Swann didn’t understand.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Source: Pixabay

I hear so many quotes attributed to Albert Einstein, it made me wonder what he really did say. So, I went searching. It’s difficult to tell from quotes what Einstein thought intuition is or where it comes from, but intuition, imagination and insight were definitely part of his ways of knowing and discovering. Here’s some of what he said about it (from The Expanded Quotable Einstein, 2000):

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

“I believe in intuition and inspiration…At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.”

“I believe in intuition and inspiration…At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.”

“My intuition was not strong enough in the field of mathematics to differentiate clearly the fundamentally important…from the rest of the more or less desirable erudition. Also, my interest in the study of nature was no doubt stronger… In this field I soon learned to sniff out that which might lead to fundamentals and to turn aside…from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind and divert from the essentials.”

“My intuition was not strong enough in the field of mathematics to differentiate clearly the fundamentally important…from the rest of the more or less desirable erudition. Also, my interest in the study of nature was no doubt stronger… In this field I soon learned to sniff out that which might lead to fundamentals and to turn aside…from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind and divert from the essentials.”

“The truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a way almost diametrically opposed to induction. The intuitive grasp of the essentials of a large complex of facts leads the scientist to the postulation of a hypothetical basic law, or several such laws. From these laws, he derives his conclusions…which can then be compared to experience. Basic laws (axioms) and conclusions together form what is called a “theory.” Every expert knows that the greatest advances in natural science…originated in this manner, and that their basis has this hypothetical character.”

“The truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a way almost diametrically opposed to induction. The intuitive grasp of the essentials of a large complex of facts leads the scientist to the postulation of a hypothetical basic law, or several such laws. From these laws, he derives his conclusions…which can then be compared to experience. Basic laws (axioms) and conclusions together form what is called a “theory.” Every expert knows that the greatest advances in natural science…originated in this manner, and that their basis has this hypothetical character.”

“All great achievements of science must start from intuitive knowledge, namely, in axioms, from which deductions are then made…Intuition is the necessary condition for the discovery of such axioms.”

“All great achievements of science must start from intuitive knowledge, namely, in axioms, from which deductions are then made…Intuition is the necessary condition for the discovery of such axioms.”

“I very rarely think in words at all. A thought comes, and I may try to express it in words afterwards.”

“I very rarely think in words at all. A thought comes, and I may try to express it in words afterwards.”

“I was sitting in the patent office in Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me: if a person falls freely, he won’t feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.”

“I was sitting in the patent office in Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me: if a person falls freely, he won’t feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.”

“I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without the use of signs (words), and, furthermore, largely unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts that is already sufficiently fixed within us…The development of the world of thinking is in effect a continual flight from wonder.”

“I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without the use of signs (words), and, furthermore, largely unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts that is already sufficiently fixed within us…The development of the world of thinking is in effect a continual flight from wonder.”

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

I’m intrigued by societies using dreams for collective purposes. Mostly those are small and indigenous. But I wonder if it’s possible in complex, industrialized, materialist Western societies, and if so, how would it work? And what could it achieve? With that questioning I found “social dreaming.” If it worked, it certainly faded, and maybe died, with its inventor. But what might we learn from it?

What is Social Dreaming?

Social dreaming, developed by Tavistock Institute consultant W. Gordon Lawrence in London and France in the late 1980s and 1990s, is a process in which individuals from a company, school, religious institution, community or any type of organization, share their night-time dreams with the group. The dreams aren’t interpreted to guide the individual who dreamed the dream. Instead, the group looks for patterns of information or meaning that show up in multiple members’ dreams. That information is important for the group as a whole.

Uncovering Hidden Knowledge & Meaning

After each person shares their dream, participants use free association to stimulate ideas and images that reveal the patterns. In his critique of Lawrence’s work, Julian Manley says the communication flow in these sessions can be similar to stream of consciousness. Also, people usually feel a sense of transcendence, as if meaning has emerged holistically, almost magically. In more structured follow-up sessions participants make sense of the new information and think about it more concretely.

The idea is that we all hold unconscious social, or shared, knowledge that dreams can reveal (Manley, p. 335). This knowing may be about culture or the social environment, including day-to-day group dynamics. The social dreaming process can make this unconscious, or implicit, knowledge explicit. When it’s brought together in the social dreaming process, the information can be used to solve the group’s problems. It can create new thinking and possibilities. At least that was Lawrence’s intent.

However, new knowledge, or unconscious information brought to light, often challenges the status quo. That’s essential if change is needed or serious problems are going to truly be solved. I’ve seen a lot of ignoring the real issues and problems at company retreats though. It takes openness and trust that can be difficult to foster in day-to-day work environments, especially competitive ones. So, when Manley says social dreaming wasn’t a financial success for Lawrence, I suspect this is one reason why.

What Happened to Social Dreaming?

Lawrence’s first book about his idea, Introduction to Social Dreaming: Transforming Thinking, was published in 2005. He worked out the process and published multiple books and articles on the subject until his death in 2013. Subsequently, some of his colleagues set up the Social Dreaming International Network and the Centre for Social Dreaming. Neither of these organizations seem to be very active, so I suspect social dreaming is defunct. (If anyone reading this hears otherwise, please let me know.)

Regardless, I think there are worthwhile takeaways.

Learning from Lawrence’s Social Dreaming Work

Takeaway 1: Ideas that run counter to culture might not be accepted

One is that any idea or process that counters cultural norms and expectations will have hard ground to try to get roots into. Social dreaming first occurred to Lawrence in 1982, several years before he was able to put it into practice. He had to leave Tavistock to do it.

Takeaway 2: Determine what information dreams can provide that waking consciousness doesn’t

When Lawrence recognized dreams among Tavistock group participants that were influenced by the group, he interpreted it within a sociological/psychological framework of group relations. Social expectations and happenings in the social world were influencing the individual psyche. It showed up in dreams. That’s an important finding. Now that we know that this happens though, would dream sharing and free association add any more information than simply paying close attention to how we’re being affected? Maybe, but it’s important to distinguish what kind of information that would be.

Takeaway 3: To use a process effectively, clarity about its assumptions and purpose is essential

Lawrence’s thinking about social dreaming can be confusing sometimes. In part, that’s probably due to working out something new. It’s an inherent part of the process. However, Manley says Lawrence sometimes included things in social dreaming that he wanted to believe, or that interested him, in ways that make it difficult to do research and development. That’s an important reminder: Clarity is essential if we’re going to be able to apply a process. Certainly to test it.

Takeaway 4: True innovation requires risk

I think much of the confusion in Lawrence’s work comes from his being torn between staying close to the socially accepted boundaries and wanting to make a leap into transcendent, spiritual, even cosmic realms. At times he equates unconscious knowledge with the infinite, quantum physics and David Bohm’s idea of the implicate order and expands the social into the universal relying on Fritjof Capra’s work. At other times, he stops short of cosmic or mystical assertions, Manley says.

That territory of consciousness does get squishy. We just don’t know that much about what it is or how it works. Also, science by-and-large doesn’t deal with the transcendental. Wanting, and needing, to maintain professional credibility, but sensing and experiencing more, Lawrence’s vacillating is understandable. This credibility risk still exists today.

Takeaway 5: Distinguish between personal/private and collective information in dreams

According to Manley, Lawrence never considers that a dream might not contribute to a collective but be only for the individual. In social dreaming, once the dream enters the group through the telling, it becomes part of the material participants work with in the shared dream space. Besides the potential distortions this could produce in shared meaning, it doesn’t allow for dreams to carry both private, personal meaning and collective meaning. It doesn’t offer ways to distinguish between dream material that’s private and material that’s from and/or for the collective, either. Understanding these distinctions, if they exist, is essential for developing a credible, effective social dreaming process.

How Might Social Dreaming Help Us Now?

The 21st Century U.S. during a global pandemic is a different time and place than Western Europe in the late 20th Century. Whether it’s ripe for some form of dreaming for social/cultural/collective purposes is unclear. If it is, it’ll be useful to know what’s been tried, what worked and what didn’t, and to what end. Social dreaming is so culturally different though, we’ll have to break the chains to do it.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

When I think of imagining, I think of it like this:

Photo Source: Canva

I have fallen in love with the imagination. And if you fall in love with the imagination, you understand that it is a free spirit. It will go anywhere, and it can do anything. —Alice Walker

If the imagination is to transcend and transform experience it has to question, to challenge, to conceive of alternatives, perhaps to the very life you are living at the moment.—Adrienne Rich

Creative, fantastical, transformative, radical and free. This kind of imagining can change our lives and our world. But it’s not the most common type of imagination, by far. And it’s not the only type that can lead to change. After reading philosophers’ debates about imagination, it makes me wonder how we’d live without this mental process, imagining takes so many forms. Sometimes we even use it unconsciously, without recognizing what we’re doing is imagining.

Here are some other important ways we use imagination that can improve our lives and facilitate organizational and social change.

One of the most common is perspective-taking. Imagination allows us to step into different views than our own and try them out. It allows us to feel how someone else might feel. I’ve thought of empathy as an emotion, but in his article about using imagination in business, Murray Hunter, consultant, entrepreneur and researcher, calls it a type of imagination. When I reflect on this, it does seem empathy includes imagining. But whatever comprises empathic perspective-taking, it can be used to project what others might do whether in business or any other area of life. Perspective-taking can give us a way to escape from circumstances, at least mentally, or to look beyond the world as it is. Imagination lets us ask what would happen if things had been different. And it helps us relate to the larger community.

Concerned about ethical decision making in business, professors Mark A. Seabright and Dennis Moberg suggest moral imagination as a way to counter corrupting influences of organizations. Moral imagination helps us think about the potential for help or harm. Who and what might be aided or hurt. They say imagination influences moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral intention and moral behavior. Imagination enhances moral sensitivity by helping us take others’ perspectives, widen the community being included for consideration, and expanding possibilities for action. Imagination keeps moral judgment flexible. It gives the ability to take into account varying rules, cases and ethos’, rather than lapsing into rigidity. Further, imagination can shape intention and action by invoking our sense of self. That can help us remain compassionate, keeping our own behavior in mind, instead of judging others by idealized standards.

Other common uses of imagination are scenario planning and strategic imagination. This type of imagining focuses on possibilities, what could be. It’s a form of visioning. It also involves attention and perception—noticing characteristics of the environment or circumstances and mentally evaluating them for opportunities to achieve the vision. Using strategic imagination, we generate alternatives, mull them over and imagine the potential consequences. Like other forms of imagination, strategic imagination requires mental flexibility. But also balanced focus. Attention that’s too open leaves us bouncing from idea to idea, unable to land on one and work it through in our mind. Focus that’s too tight blocks possibilities and can even become obsession.

A form of imagination that’s close to my heart is what sociologist C. Wright Mills called the sociological imagination. It’s not something unique to sociologists. Sociology done without it though can be boring and add little insight. Sociological imagination focuses on big social problems, sees how they relate to history and socio-cultural systems, and how these macro-level forces affect individuals’ beliefs, values, character and behavior. It can go the opposite way too, imagining how individuals affect human systems. Sociological imagination allows us to move from individual meaning-making up through small groups, communities, industries, societies and even global systems and see effects at multiple levels simultaneously. It’s a remarkably flexible mental tool.

Another of my favorites is daydreaming. I hadn’t thought about this as imagination, but of course, what else would it be? According to Hunter, surplus attention and unguided imagination—free association—allows our right hemisphere to take charge. It gathers a range of information from our memory and recombines it, makes new meaning from it, or helps us see a problem, issue or the environment from a different perspective. Others see daydreaming as a passive form of imagining that involves emotion, like superhero fantasies or aspirations. Daydreaming can bring pleasure and can be a way to rehearse potential action.

Imagination involves divergent thinking. This mental attitude and aptitude for roaming across boundaries, taking in information from multiple places and in many forms, is unlike logical thinking which stays within a narrow path. Imagination lends itself to thought experiments, a form of research we don’t hear much about. It was used by Galileo, Descartes, Newton and Leibniz and played a huge role in quantum mechanics and relativity. Thought experiments are used in philosophy, physics, economics and history and seem like a reasonable way to try out social systems change.

After my initial trip through readings on imagination, I now have a lot more questions about it. How does imagination relate to memory? To dreams? To perception? In fantasy, we can totally disregard the rules of society, science and nature, so is perception involved in this kind of imagining? Does imagination itself have power to influence or can that happen only when enacted by a physical body in the material world? Remember, Alice Walker says, imagination can go anywhere. It can do anything.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Source: Deposit Photos

[Note: This post is longer than most.] A few things I’ve noticed in my reading make me think about how culture facilitates or limits what we know and can know. It affects how we interpret experience. I think we might even miss subtle sensory experience when our culture has no language or explanatory framework from which to recognize and express it. I’m thinking specifically about intuition and heart.

In “Intuition: Myth or Decision Making Tool?,” Marta Sinclair and Neal M. Ashkanasy review the literature on intuition to figure out how to measure it in business decision-making. Researching intuition in Western culture is tough for two reasons: 1) intuition isn’t clearly defined, and 2) people lack the vocabulary to communicate the experience. They say the lack of language “may have been caused by a decline in contemplative approaches that use introspection as a valid investigative method” (p. 5) and the language to describe intuition has disappeared from secular Western culture. So, we have an ephemeral experience in a culture without language to express it.

Then we’ve got some reviving to do, or a new direction to carve.

What do we mean by intuition?

A few years ago I read Daniel Kahneman’s influential book Thinking Fast and Slow. I was reading it then because a major part of my work involved getting people to use data in decision making and that doesn’t come easy to most. Kahneman says people have two information processing systems, the intuitive (fast) and analytical (slow) and the analytical is more accurate. What he considers intuitive…. I remember thinking, ugh! That’s not intuition.

That’s a combination of instinct, personal preference, internalized culture and tacit expertise. Instinct, that quick, high-alert state is something all animals have. For people, it doesn’t carry much information, just OK or not OK, essentially. Internalized culture, that’s taken for granted beliefs and values we act on without even recognizing it they’re so engrained and below conscious awareness. It includes stereotypes and implicit biases of all sorts. So sure, decisions made based in this jumble may very well be wrong. The expertise form of intuition is typically thought to be experientially accrued knowledge retrieved through pattern recognition. This expertise form, I’ve experienced on the job. Maybe it’s what comes into play in creative and scientific breakthroughs that appear in dreams or reverie.

As you can tell, I’m not on board with what Kahneman considers intuitive. I agree we often use this jumble of unconscious stimuli and material that bubbles up for our shorthand, quick decisions. But lumping it all together and calling it intuition, or intuitive decision making, confuses and feeds into Western culture’s denigration of intuition. Further, this jumble in no way matches my experience of intuition. In fact, in my experience it’s intuition that cuts through this jumble and shines a light on the truth, or essence of a situation.

East West Consciousness Chasm

That makes me think of another instance where Western culture doesn’t have the language, and maybe not the experience either. At an MIT symposium that brought together Western scientists and Buddhist contemplatives jointly studying the nature of mind (Waking, Dreaming, Being by philosophy professor Evan Thompson), the enduring debate about whether consciousness is generated by the brain or whether it transcends the brain came up.

Most neuroscientists believe the former. Buddhist tradition holds to the latter. Buddhist contemplative adepts in some traditions experience in meditation what they call “pure awareness” or “luminous consciousness,” a clear, resonant knowing that contains no mental imagery or sensory stimuli. Harvard’s history of science professor Anne Harrington pointed out that Western science has no concept like pure awareness. Consequently, she questioned how brain scientists and Buddhists can work together on this given that lack. Is it an uncrossable chasm?

The Dalai Lama doesn’t think so. He’s questioning whether there might be some physical basis for the experience. Thompson too thinks it can be done. But, scientists need to incorporate contemplative methods–though they don’t have to bring along Buddhist philosophy–and Buddhists need to weigh their experience in the context of what scientists have learned. I’ve experienced what I might call “pure awareness” or “luminosity,” so undoubtedly others in Western culture have too. It may or may not be qualitatively the same as what the Buddhists experience, but it should be close enough to serve as a bridge. I don’t have language for it though other than luminosity—which in science has specific meanings that I don’t intend.

Defining Intuition

Back to what intuition is. Sinclair and Ashkanasy say intuition has three characteristics: “1) intuitive events originate beyond consciousness, 2) information is processed holistically, and 3) intuitive perceptions are frequently accompanied by emotion (p. 7).” The emotion though may be more of a feeling or sense than what we typically think of as emotion–happy, sad, angry. There’s another place where perhaps our everyday language is inadequate.

Anyway, putting these three components together, they define intuition as “a non-sequential information processing mode, which comprises both cognitive and affective elements and results in direct knowing without any conscious reasoning.” They recognize a transcendent or transpersonal component of intuition (like the Buddhists’ view of pure awareness), but just note it given the difficulty it adds to understanding intuition and measuring it. To avoid excluding it though, they use the term “non-conscious” as a catch-all for all levels or states of awareness that aren’t conscious. I can go with their definition. Their wording is clunky for ordinary use though.

Jeffrey Mishlove, President of the Intuition Network, uses a dictionary definition of intuition to try to get to the heart of the matter: “direct perception of truth, fact, etc. independent of any reasoning process; immediate apprehension,” “a keen and quick insight” and “knowing without knowing how you know.”

That’s better. If we don’t lose the affective, sensory part. Although even that doesn’t exist with “pure awareness.” So for now, I’ll go with perceiving new information immediately, directly, by non-conscious means.

Intuitive and Analytical Knowing

The last piece I’ll bring in here that made me think about the confusion or absence of language happened while I was listening to Mishlove interview a medium. An audience member wanted to know how to distinguish real, intuitive information from random thoughts. The medium’s answer was listen to your heart. It will tell you which way to go. The spirits don’t talk to the analytical mind. He said he thinks people don’t know how to distinguish heart, how they feel, from intuitive information. The intuitive information is resonant.

Two thoughts here.

One: I wonder how many scientists have experienced intuition in the transpersonal sense. Some have, I know. It seems they’d have an easier time crossing the investigative bridge. But then, would scientists who haven’t had experience accept what’s learned? Regardless of its quality, parapsychologists’ investigations have repeatedly been called into question and dismissed (though the credibility of cumulative findings over decades is beginning to be accepted).

The medium’s statement also makes me wonder whether the traditional experimental, objectivist science approach or attitude inhibits intuition from operating or being observed. Based solely on my personal experience, the analytical and intuitive are complementary and these two ways of knowing work differently and they feel different. I’ll talk about the knowing process here and save the feeling part for a later paragraph.

For me, it’s been a lifelong conflict and testing to learn to let the analytical and intuitive work together, rather than competing. Or the analytical extinguishing the intuitive. The intuitive doesn’t vie for control. That’s the exact opposite of its nature. It’s an open, receptive state. The analytical bears down, picks apart, pushes and pulls to figure things out. The intuitive grasps information whole. If there’s a process, it’s so subtle I don’t recognize it. It seemingly just appears. (Which would be a more conducive state for spirit communication—if indeed that’s what it is— than the analytical state). I can set conditions to make intuition more likely though. The analytical mind can verify or extend intuitive insight. The intuitive mind can get the analytical mind out of the ruts it can dig itself into and expand the view. When they work in parallel, magic can happen.

After reading Sinclair and Ashkanasy’s take on the decline of contemplative practices, I wondered, would formally learning contemplative practices make coming to that place of analytical-intuitive complementarity faster and easier? Probably. If I’d have known such training exists, I may have jumped in to get myself out of the anguish the split between these two ways of knowing caused me sometimes. But then I wouldn’t have the experience of trial and error and learning without an established worldview’s way of doing it.

(Digression: This is why I can see what Thompson means when he says Western scientists can learn the contemplative methods, but don’t have to accept the Buddhist philosophy. In fact, contemplative inquiry methods existed in Western culture prior to the ascendancy of empiricism. And, what about “thought experiments”? That might not be considered contemplative, but it’s certainly a different method, a method of the imagination—a component of the mind. Thompson thinks “neurophenomenology”—combining phenomenology’s intricate study of experience from within the experience, with neuroscientists’ imaging of the brain is a way for Buddhists and scientists to “create a new and unprecedented kind of self-knowledge” (p. xix).

Sinclair and Ashkanasy give a terrific description of the intuitive and analytical:

“Each mode supports a different decision-making approach, suitable for a different type of problem-solving. The analytical approach of the rational mode is intentional, mostly verbal, and relatively affect-free. It adheres to abstract rules of analysis and logic and, as such, can yield precise answers to complex factual problems. (Not unlike Kahneman’s description)

The intuitive approach of the experiential mode operates quite differently. As an automatic, preconscious mode, it functions in a holistic, mostly averbal manner and maintains close links to affect. It is context-specific and explains complexity through associations and metaphors. Therefore, it often operates by approximation, which is intrinsically imprecise” (p. 12). That “imprecise” part bothers empiricist scientists, and it bothers the analytical mind in general. The one part of their description I question is intuition as “context-specific.” I’ve had too many out-of-the-blue flashes of insight about big-picture issues happen at all kinds of times and in all kinds of places to peg it to any specific context. It’s more likely in some circumstances or places though.

Intuitive Heart

Two: It’s been several paragraphs, but if you’re still with me, remember the medium said he thinks people don’t know how to distinguish the emotional heart from the heart’s intuition. It seems to me this is a place where Western secular culture doesn’t have language to distinguish well, so it concerns me when I hear “listen to your heart.” In American culture, we think “heart” means Hallmark. That can easily slip into—whatever I feel, it’s intuitive and therefore the right thing to do. Which can be destructive and off-base and definitely not intuitive. It can also lead people to believe love is the pinnacle of everything. Not dissing love, but I’ve seen that belief so over-valued that people turn themselves into pretzels and doormats trying to be always loving. An 80-year-old friend once told me she thinks we need a lot more words for love, because that one word subsumes too many different feelings. (Maybe an issue for another post someday).

To me, heart intuition feels more like an awareness, a subtle opening of inner space than an emotion, or even a feeling. It’s more likely to happen when I’m relaxed, joyful, grateful, appreciative, even loving. Logic and obsession feel centered in my head. Intuition usually doesn’t. I may not sense it near my physical heart either, if I try to locate it in physical space. That makes me think the body may have multiple receptors, even non-physical ones. What language do we use to communicate this sensing that distinguishes it from the emotion Western culture associates with the heart—like love, compassion, sadness and grief?

Emotion and Intuition

Sinclair and Ashkanasy say emotion and intuition have a complicated relationship. Positive emotion, like joy or enthusiasm, can open channels to intuitive insight. (This makes me think about ritual generating this kind of emotion, and its use in some indigenous and religious practices, but that’s for a different post.) Negative emotion’s influence on intuition isn’t as straightforward. Some kinds or degrees of emotion can block or distort intuitive information. Fear, is a good example. But sometimes the emotion may come after an intuitive insight, such as relief. I’ve never thought of “relief” as an emotion, but…there’s a lot in this research that makes me re-think.

In research for her book Extraordinary Knowing, psychologist Elizabeth Lloyd Mayer talked with a professional intuitive who said she was afraid when she first started noticing her abilities: “Intuition requires being receptive to reality as it is, not how we’d like it to be so why go there when cognitive reasoning assures us that reality is predictable?” (p. 129). It’s uncomfortable, even threatening.

The medium I listened to recently said people don’t understand how what he does works and they can be hurtful. (Which is why I’m not linking to his interview. He no longer gives public readings because of people’s abuse.) In my experience, intuitive insights can be uncomfortable too. You may learn things you’d rather not know about yourself or be pointed in a direction that isn’t the one you want or expect. The intuitive in Mayer’s book thinks this uncertainty and upset may be what’s going on with scientists who blast any other means of knowing besides cognitive reasoning. Essentially, a defense. But she says, “Reality goes on anyway, regardless of who’s noticing.”

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

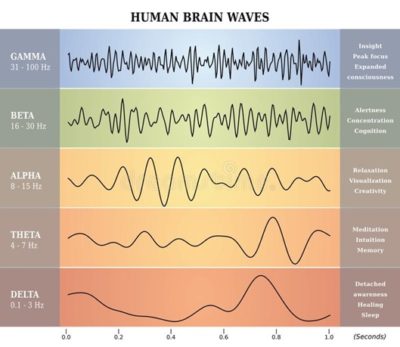

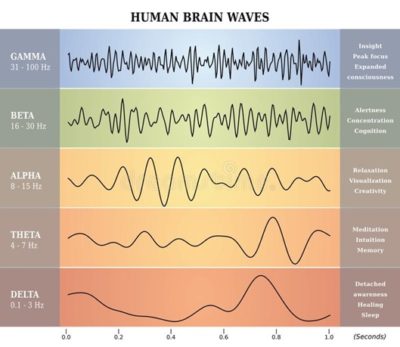

Source: Myndlift

Most of us have experienced it—the in-tuneness of romantic love, the “flow” of teamwork that’s going well. When we’re in synch with someone, we often say we’re on the same wavelength. Even in large groups—marching together, an audience captivated by a moving performance, or dancing or chanting—we can feel this sense of connection. What’s going on in our bodies when these states happen? Many spiritual traditions say we’re not separate beings. That we’re all connected. Can it be that we really are physiologically connected with each other?

Where is the Mind?

Until the last 15 or so years, neuroscientists said it’s an irrefutable tenet that the mind is only inside the head. The brain’s electrical impulses travel through the body, but not outside the skull. The signals are too weak to penetrate it. That idea excludes the possibility of direct human brain to brain communication. But, can it happen some other way? Our everyday experience, like the ones noted above or our skin prickling when someone not yet seen is nearby, makes it difficult to just accept that we’re solo beings encased in skin and bone.

Many neuroscientists still hold to that mind-inside-the-head assumption, but “social cognitive neuroscientists” are parting ways with that idea. They’re testing what happens brain to brain during real-time social interaction. In these experiments you’ll see people singing together or playing guitar duets. Maybe they’ll jointly put a puzzle together or play a game. Whatever the social activity, they’ll be wearing electrodes on their scalp that feed data from their brainwaves, blood flow and oxygenation into a computer while they play together.

When Do Brains Synch?

In the journal Neuroscience of Consciousness (June 2020), Ana Lucía Valencia and Tom Froese summarize what’s been learned across many studies. The most central finding? Brains connect. Researchers can see neural synching between pairs of people. The same brain areas light up and brain waves entrain. You might think, of course. Those parts of the brain are needed to do the task. But this synching isn’t. It emerges out of the qualities of the social interaction. Without that interaction, it doesn’t exist.

Neural synching appears when people are cooperating. It’s absent when they’re competing, and when they’re working separately—yet simultaneously—on a task. Co-pilots are an interesting example. During takeoff and landing—when they need intense cooperation—their brains synchronize. During the rest of the flight, not. In another study, after hearing a signal, paired subjects were supposed to silently count to 10 then simultaneously push a button. In repeated tests, as participants’ brains became more synched during counting, “the time interval between their button-presses was shorter” (p. 4). Other studies show this same convergence. Clearly, performance coordination improves.

What if we could use this to accelerate learning? Could we pair an expert and a novice on a skill and see the novice improve faster than through traditional methods? What about developing teams, especially where highly efficient fine motor precision and coordination is required? Surgery, for example.

Enjoying and Engaging with Other People

It seems when people need to work together, or enjoy collaborating, their brainwaves begin to synchronize. In a card game experiment, “believing” you’re part of the same team facilitated synching. Most of these studies don’t include participants’ subjective experience, but when they do there’s a clear correspondence between feelings and brain synchrony. For example, pairs who “felt” cooperative showed higher levels of neural synching while cooperating. Somehow, researchers got a class of 12 high school students to agree to inter-brain synchrony testing across a semester. Based on 11 class sessions, researchers could see synchrony associated with feelings of engagement, affinity, empathy and social closeness.

What We Believe Can Affect Whether Brains Synch

On the other hand, some people, and some situations, didn’t synch. Not all of the students in the classroom experiment synched with the whole group. People experiencing attachment anxiety or pain were less likely to connect in this way. As we would expect, people on the autism spectrum didn’t synchronize. Neither did people who were being competitive. People didn’t bond with a computer either. Even if they were paired with a human partner but seated at a computer and told they were interacting with the computer—when in reality they were interacting with each other—their brains didn’t synch. What they believed affected their neural activity.

Clearly, there’s a lot going on below the surface that we’re not consciously aware of. That’s not new. Psychologists and sociologists have known this for a long time. Their studies have included the subconscious, symbols, meaning and perception, for instance. Some of the “social neuroscientists” are weaving their physiological findings into what’s known behaviorally, helping to flesh out the complexity of who we are and how we experience the world together.

What About Implicit and Explicit Group Intent?

Another thing that interests me from the Valencia and Froese article is collective intent. They don’t really discuss it, but presumably they’re referring to the pairs of participants intending to achieve the tasks in the experiments. The classroom study involved a dozen people. In this natural setting, intent is more multifaceted. Learning the subject matter is the most explicit purpose, but there’s social learning going on too. And with 12 people, instead of two, there’s bound to be other intents, even if implicit.

What about even larger groups—100 or 1,000 people? If there was an explicit intent, would the same brain synching happen? We know from behavioral studies of group dynamics that the experience is different with 6-10 people, for instance, than with 2-3 or with 20-30. Yet there are times when it seems like a wave catches, enveloping even millions of people. That condition alone may be different than an intentionally designed test of 100 or 1,000 people, but it’s one of many questions that occur to me as I think about interdisciplinary investigation.

Would Brains Synch if People Work Together Remotely?

The logistics of testing this many people simultaneously would likely be difficult. Even with pairs, these are complicated, expensive studies to do given the necessary equipment, expertise and the need to shield subjects from other forms of electrical interference. The classroom study was done with cheaper, portable technology that’s now available to consumers. Signal quality is sacrificed, but it might work well enough for some tests.

I wonder if brain synching experiments could be done remotely? Would the brains of humans engaged in a shared task without being in the same room still synchronize? Neuroscientists don’t yet know “how” the synching happens, just that it does. Some think perceptual cues—like eye contact, facial expression and voice inflection, are necessary for brains to entrain. That suggests proximity is necessary. But then, we do have Zoom. Would that work? On the other hand, some of the findings involved what people “believe.” So, if we believe we’re working with others remotely, and we are, might brains still synch? Given COVID19 social distancing, it seems like an excellent time to test it and find out.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist