Source: Myndlift

Most of us have experienced it—the in-tuneness of romantic love, the “flow” of teamwork that’s going well. When we’re in synch with someone, we often say we’re on the same wavelength. Even in large groups—marching together, an audience captivated by a moving performance, or dancing or chanting—we can feel this sense of connection. What’s going on in our bodies when these states happen? Many spiritual traditions say we’re not separate beings. That we’re all connected. Can it be that we really are physiologically connected with each other?

Where is the Mind?

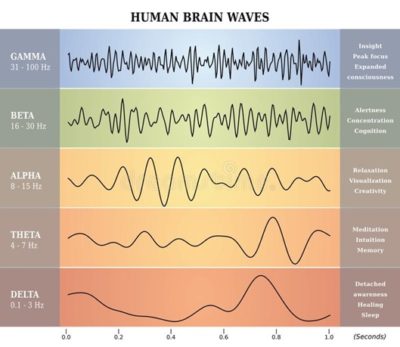

Until the last 15 or so years, neuroscientists said it’s an irrefutable tenet that the mind is only inside the head. The brain’s electrical impulses travel through the body, but not outside the skull. The signals are too weak to penetrate it. That idea excludes the possibility of direct human brain to brain communication. But, can it happen some other way? Our everyday experience, like the ones noted above or our skin prickling when someone not yet seen is nearby, makes it difficult to just accept that we’re solo beings encased in skin and bone.

Many neuroscientists still hold to that mind-inside-the-head assumption, but “social cognitive neuroscientists” are parting ways with that idea. They’re testing what happens brain to brain during real-time social interaction. In these experiments you’ll see people singing together or playing guitar duets. Maybe they’ll jointly put a puzzle together or play a game. Whatever the social activity, they’ll be wearing electrodes on their scalp that feed data from their brainwaves, blood flow and oxygenation into a computer while they play together.

When Do Brains Synch?

In the journal Neuroscience of Consciousness (June 2020), Ana Lucía Valencia and Tom Froese summarize what’s been learned across many studies. The most central finding? Brains connect. Researchers can see neural synching between pairs of people. The same brain areas light up and brain waves entrain. You might think, of course. Those parts of the brain are needed to do the task. But this synching isn’t. It emerges out of the qualities of the social interaction. Without that interaction, it doesn’t exist.

Neural synching appears when people are cooperating. It’s absent when they’re competing, and when they’re working separately—yet simultaneously—on a task. Co-pilots are an interesting example. During takeoff and landing—when they need intense cooperation—their brains synchronize. During the rest of the flight, not. In another study, after hearing a signal, paired subjects were supposed to silently count to 10 then simultaneously push a button. In repeated tests, as participants’ brains became more synched during counting, “the time interval between their button-presses was shorter” (p. 4). Other studies show this same convergence. Clearly, performance coordination improves.

What if we could use this to accelerate learning? Could we pair an expert and a novice on a skill and see the novice improve faster than through traditional methods? What about developing teams, especially where highly efficient fine motor precision and coordination is required? Surgery, for example.

Enjoying and Engaging with Other People

It seems when people need to work together, or enjoy collaborating, their brainwaves begin to synchronize. In a card game experiment, “believing” you’re part of the same team facilitated synching. Most of these studies don’t include participants’ subjective experience, but when they do there’s a clear correspondence between feelings and brain synchrony. For example, pairs who “felt” cooperative showed higher levels of neural synching while cooperating. Somehow, researchers got a class of 12 high school students to agree to inter-brain synchrony testing across a semester. Based on 11 class sessions, researchers could see synchrony associated with feelings of engagement, affinity, empathy and social closeness.

What We Believe Can Affect Whether Brains Synch

On the other hand, some people, and some situations, didn’t synch. Not all of the students in the classroom experiment synched with the whole group. People experiencing attachment anxiety or pain were less likely to connect in this way. As we would expect, people on the autism spectrum didn’t synchronize. Neither did people who were being competitive. People didn’t bond with a computer either. Even if they were paired with a human partner but seated at a computer and told they were interacting with the computer—when in reality they were interacting with each other—their brains didn’t synch. What they believed affected their neural activity.

Clearly, there’s a lot going on below the surface that we’re not consciously aware of. That’s not new. Psychologists and sociologists have known this for a long time. Their studies have included the subconscious, symbols, meaning and perception, for instance. Some of the “social neuroscientists” are weaving their physiological findings into what’s known behaviorally, helping to flesh out the complexity of who we are and how we experience the world together.

What About Implicit and Explicit Group Intent?

Another thing that interests me from the Valencia and Froese article is collective intent. They don’t really discuss it, but presumably they’re referring to the pairs of participants intending to achieve the tasks in the experiments. The classroom study involved a dozen people. In this natural setting, intent is more multifaceted. Learning the subject matter is the most explicit purpose, but there’s social learning going on too. And with 12 people, instead of two, there’s bound to be other intents, even if implicit.

What about even larger groups—100 or 1,000 people? If there was an explicit intent, would the same brain synching happen? We know from behavioral studies of group dynamics that the experience is different with 6-10 people, for instance, than with 2-3 or with 20-30. Yet there are times when it seems like a wave catches, enveloping even millions of people. That condition alone may be different than an intentionally designed test of 100 or 1,000 people, but it’s one of many questions that occur to me as I think about interdisciplinary investigation.

Would Brains Synch if People Work Together Remotely?

The logistics of testing this many people simultaneously would likely be difficult. Even with pairs, these are complicated, expensive studies to do given the necessary equipment, expertise and the need to shield subjects from other forms of electrical interference. The classroom study was done with cheaper, portable technology that’s now available to consumers. Signal quality is sacrificed, but it might work well enough for some tests.

I wonder if brain synching experiments could be done remotely? Would the brains of humans engaged in a shared task without being in the same room still synchronize? Neuroscientists don’t yet know “how” the synching happens, just that it does. Some think perceptual cues—like eye contact, facial expression and voice inflection, are necessary for brains to entrain. That suggests proximity is necessary. But then, we do have Zoom. Would that work? On the other hand, some of the findings involved what people “believe.” So, if we believe we’re working with others remotely, and we are, might brains still synch? Given COVID19 social distancing, it seems like an excellent time to test it and find out.