by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

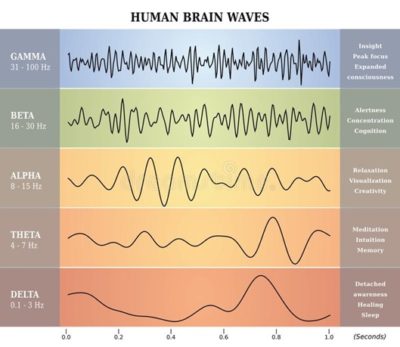

Source: Deposit Photos

[Note: This post is longer than most.] A few things I’ve noticed in my reading make me think about how culture facilitates or limits what we know and can know. It affects how we interpret experience. I think we might even miss subtle sensory experience when our culture has no language or explanatory framework from which to recognize and express it. I’m thinking specifically about intuition and heart.

In “Intuition: Myth or Decision Making Tool?,” Marta Sinclair and Neal M. Ashkanasy review the literature on intuition to figure out how to measure it in business decision-making. Researching intuition in Western culture is tough for two reasons: 1) intuition isn’t clearly defined, and 2) people lack the vocabulary to communicate the experience. They say the lack of language “may have been caused by a decline in contemplative approaches that use introspection as a valid investigative method” (p. 5) and the language to describe intuition has disappeared from secular Western culture. So, we have an ephemeral experience in a culture without language to express it.

Then we’ve got some reviving to do, or a new direction to carve.

What do we mean by intuition?

A few years ago I read Daniel Kahneman’s influential book Thinking Fast and Slow. I was reading it then because a major part of my work involved getting people to use data in decision making and that doesn’t come easy to most. Kahneman says people have two information processing systems, the intuitive (fast) and analytical (slow) and the analytical is more accurate. What he considers intuitive…. I remember thinking, ugh! That’s not intuition.

That’s a combination of instinct, personal preference, internalized culture and tacit expertise. Instinct, that quick, high-alert state is something all animals have. For people, it doesn’t carry much information, just OK or not OK, essentially. Internalized culture, that’s taken for granted beliefs and values we act on without even recognizing it they’re so engrained and below conscious awareness. It includes stereotypes and implicit biases of all sorts. So sure, decisions made based in this jumble may very well be wrong. The expertise form of intuition is typically thought to be experientially accrued knowledge retrieved through pattern recognition. This expertise form, I’ve experienced on the job. Maybe it’s what comes into play in creative and scientific breakthroughs that appear in dreams or reverie.

As you can tell, I’m not on board with what Kahneman considers intuitive. I agree we often use this jumble of unconscious stimuli and material that bubbles up for our shorthand, quick decisions. But lumping it all together and calling it intuition, or intuitive decision making, confuses and feeds into Western culture’s denigration of intuition. Further, this jumble in no way matches my experience of intuition. In fact, in my experience it’s intuition that cuts through this jumble and shines a light on the truth, or essence of a situation.

East West Consciousness Chasm

That makes me think of another instance where Western culture doesn’t have the language, and maybe not the experience either. At an MIT symposium that brought together Western scientists and Buddhist contemplatives jointly studying the nature of mind (Waking, Dreaming, Being by philosophy professor Evan Thompson), the enduring debate about whether consciousness is generated by the brain or whether it transcends the brain came up.

Most neuroscientists believe the former. Buddhist tradition holds to the latter. Buddhist contemplative adepts in some traditions experience in meditation what they call “pure awareness” or “luminous consciousness,” a clear, resonant knowing that contains no mental imagery or sensory stimuli. Harvard’s history of science professor Anne Harrington pointed out that Western science has no concept like pure awareness. Consequently, she questioned how brain scientists and Buddhists can work together on this given that lack. Is it an uncrossable chasm?

The Dalai Lama doesn’t think so. He’s questioning whether there might be some physical basis for the experience. Thompson too thinks it can be done. But, scientists need to incorporate contemplative methods–though they don’t have to bring along Buddhist philosophy–and Buddhists need to weigh their experience in the context of what scientists have learned. I’ve experienced what I might call “pure awareness” or “luminosity,” so undoubtedly others in Western culture have too. It may or may not be qualitatively the same as what the Buddhists experience, but it should be close enough to serve as a bridge. I don’t have language for it though other than luminosity—which in science has specific meanings that I don’t intend.

Defining Intuition

Back to what intuition is. Sinclair and Ashkanasy say intuition has three characteristics: “1) intuitive events originate beyond consciousness, 2) information is processed holistically, and 3) intuitive perceptions are frequently accompanied by emotion (p. 7).” The emotion though may be more of a feeling or sense than what we typically think of as emotion–happy, sad, angry. There’s another place where perhaps our everyday language is inadequate.

Anyway, putting these three components together, they define intuition as “a non-sequential information processing mode, which comprises both cognitive and affective elements and results in direct knowing without any conscious reasoning.” They recognize a transcendent or transpersonal component of intuition (like the Buddhists’ view of pure awareness), but just note it given the difficulty it adds to understanding intuition and measuring it. To avoid excluding it though, they use the term “non-conscious” as a catch-all for all levels or states of awareness that aren’t conscious. I can go with their definition. Their wording is clunky for ordinary use though.

Jeffrey Mishlove, President of the Intuition Network, uses a dictionary definition of intuition to try to get to the heart of the matter: “direct perception of truth, fact, etc. independent of any reasoning process; immediate apprehension,” “a keen and quick insight” and “knowing without knowing how you know.”

That’s better. If we don’t lose the affective, sensory part. Although even that doesn’t exist with “pure awareness.” So for now, I’ll go with perceiving new information immediately, directly, by non-conscious means.

Intuitive and Analytical Knowing

The last piece I’ll bring in here that made me think about the confusion or absence of language happened while I was listening to Mishlove interview a medium. An audience member wanted to know how to distinguish real, intuitive information from random thoughts. The medium’s answer was listen to your heart. It will tell you which way to go. The spirits don’t talk to the analytical mind. He said he thinks people don’t know how to distinguish heart, how they feel, from intuitive information. The intuitive information is resonant.

Two thoughts here.

One: I wonder how many scientists have experienced intuition in the transpersonal sense. Some have, I know. It seems they’d have an easier time crossing the investigative bridge. But then, would scientists who haven’t had experience accept what’s learned? Regardless of its quality, parapsychologists’ investigations have repeatedly been called into question and dismissed (though the credibility of cumulative findings over decades is beginning to be accepted).

The medium’s statement also makes me wonder whether the traditional experimental, objectivist science approach or attitude inhibits intuition from operating or being observed. Based solely on my personal experience, the analytical and intuitive are complementary and these two ways of knowing work differently and they feel different. I’ll talk about the knowing process here and save the feeling part for a later paragraph.

For me, it’s been a lifelong conflict and testing to learn to let the analytical and intuitive work together, rather than competing. Or the analytical extinguishing the intuitive. The intuitive doesn’t vie for control. That’s the exact opposite of its nature. It’s an open, receptive state. The analytical bears down, picks apart, pushes and pulls to figure things out. The intuitive grasps information whole. If there’s a process, it’s so subtle I don’t recognize it. It seemingly just appears. (Which would be a more conducive state for spirit communication—if indeed that’s what it is— than the analytical state). I can set conditions to make intuition more likely though. The analytical mind can verify or extend intuitive insight. The intuitive mind can get the analytical mind out of the ruts it can dig itself into and expand the view. When they work in parallel, magic can happen.

After reading Sinclair and Ashkanasy’s take on the decline of contemplative practices, I wondered, would formally learning contemplative practices make coming to that place of analytical-intuitive complementarity faster and easier? Probably. If I’d have known such training exists, I may have jumped in to get myself out of the anguish the split between these two ways of knowing caused me sometimes. But then I wouldn’t have the experience of trial and error and learning without an established worldview’s way of doing it.

(Digression: This is why I can see what Thompson means when he says Western scientists can learn the contemplative methods, but don’t have to accept the Buddhist philosophy. In fact, contemplative inquiry methods existed in Western culture prior to the ascendancy of empiricism. And, what about “thought experiments”? That might not be considered contemplative, but it’s certainly a different method, a method of the imagination—a component of the mind. Thompson thinks “neurophenomenology”—combining phenomenology’s intricate study of experience from within the experience, with neuroscientists’ imaging of the brain is a way for Buddhists and scientists to “create a new and unprecedented kind of self-knowledge” (p. xix).

Sinclair and Ashkanasy give a terrific description of the intuitive and analytical:

“Each mode supports a different decision-making approach, suitable for a different type of problem-solving. The analytical approach of the rational mode is intentional, mostly verbal, and relatively affect-free. It adheres to abstract rules of analysis and logic and, as such, can yield precise answers to complex factual problems. (Not unlike Kahneman’s description)

The intuitive approach of the experiential mode operates quite differently. As an automatic, preconscious mode, it functions in a holistic, mostly averbal manner and maintains close links to affect. It is context-specific and explains complexity through associations and metaphors. Therefore, it often operates by approximation, which is intrinsically imprecise” (p. 12). That “imprecise” part bothers empiricist scientists, and it bothers the analytical mind in general. The one part of their description I question is intuition as “context-specific.” I’ve had too many out-of-the-blue flashes of insight about big-picture issues happen at all kinds of times and in all kinds of places to peg it to any specific context. It’s more likely in some circumstances or places though.

Intuitive Heart

Two: It’s been several paragraphs, but if you’re still with me, remember the medium said he thinks people don’t know how to distinguish the emotional heart from the heart’s intuition. It seems to me this is a place where Western secular culture doesn’t have language to distinguish well, so it concerns me when I hear “listen to your heart.” In American culture, we think “heart” means Hallmark. That can easily slip into—whatever I feel, it’s intuitive and therefore the right thing to do. Which can be destructive and off-base and definitely not intuitive. It can also lead people to believe love is the pinnacle of everything. Not dissing love, but I’ve seen that belief so over-valued that people turn themselves into pretzels and doormats trying to be always loving. An 80-year-old friend once told me she thinks we need a lot more words for love, because that one word subsumes too many different feelings. (Maybe an issue for another post someday).

To me, heart intuition feels more like an awareness, a subtle opening of inner space than an emotion, or even a feeling. It’s more likely to happen when I’m relaxed, joyful, grateful, appreciative, even loving. Logic and obsession feel centered in my head. Intuition usually doesn’t. I may not sense it near my physical heart either, if I try to locate it in physical space. That makes me think the body may have multiple receptors, even non-physical ones. What language do we use to communicate this sensing that distinguishes it from the emotion Western culture associates with the heart—like love, compassion, sadness and grief?

Emotion and Intuition

Sinclair and Ashkanasy say emotion and intuition have a complicated relationship. Positive emotion, like joy or enthusiasm, can open channels to intuitive insight. (This makes me think about ritual generating this kind of emotion, and its use in some indigenous and religious practices, but that’s for a different post.) Negative emotion’s influence on intuition isn’t as straightforward. Some kinds or degrees of emotion can block or distort intuitive information. Fear, is a good example. But sometimes the emotion may come after an intuitive insight, such as relief. I’ve never thought of “relief” as an emotion, but…there’s a lot in this research that makes me re-think.

In research for her book Extraordinary Knowing, psychologist Elizabeth Lloyd Mayer talked with a professional intuitive who said she was afraid when she first started noticing her abilities: “Intuition requires being receptive to reality as it is, not how we’d like it to be so why go there when cognitive reasoning assures us that reality is predictable?” (p. 129). It’s uncomfortable, even threatening.

The medium I listened to recently said people don’t understand how what he does works and they can be hurtful. (Which is why I’m not linking to his interview. He no longer gives public readings because of people’s abuse.) In my experience, intuitive insights can be uncomfortable too. You may learn things you’d rather not know about yourself or be pointed in a direction that isn’t the one you want or expect. The intuitive in Mayer’s book thinks this uncertainty and upset may be what’s going on with scientists who blast any other means of knowing besides cognitive reasoning. Essentially, a defense. But she says, “Reality goes on anyway, regardless of who’s noticing.”

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

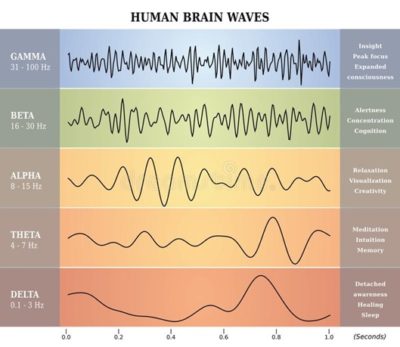

Source: Myndlift

Most of us have experienced it—the in-tuneness of romantic love, the “flow” of teamwork that’s going well. When we’re in synch with someone, we often say we’re on the same wavelength. Even in large groups—marching together, an audience captivated by a moving performance, or dancing or chanting—we can feel this sense of connection. What’s going on in our bodies when these states happen? Many spiritual traditions say we’re not separate beings. That we’re all connected. Can it be that we really are physiologically connected with each other?

Where is the Mind?

Until the last 15 or so years, neuroscientists said it’s an irrefutable tenet that the mind is only inside the head. The brain’s electrical impulses travel through the body, but not outside the skull. The signals are too weak to penetrate it. That idea excludes the possibility of direct human brain to brain communication. But, can it happen some other way? Our everyday experience, like the ones noted above or our skin prickling when someone not yet seen is nearby, makes it difficult to just accept that we’re solo beings encased in skin and bone.

Many neuroscientists still hold to that mind-inside-the-head assumption, but “social cognitive neuroscientists” are parting ways with that idea. They’re testing what happens brain to brain during real-time social interaction. In these experiments you’ll see people singing together or playing guitar duets. Maybe they’ll jointly put a puzzle together or play a game. Whatever the social activity, they’ll be wearing electrodes on their scalp that feed data from their brainwaves, blood flow and oxygenation into a computer while they play together.

When Do Brains Synch?

In the journal Neuroscience of Consciousness (June 2020), Ana Lucía Valencia and Tom Froese summarize what’s been learned across many studies. The most central finding? Brains connect. Researchers can see neural synching between pairs of people. The same brain areas light up and brain waves entrain. You might think, of course. Those parts of the brain are needed to do the task. But this synching isn’t. It emerges out of the qualities of the social interaction. Without that interaction, it doesn’t exist.

Neural synching appears when people are cooperating. It’s absent when they’re competing, and when they’re working separately—yet simultaneously—on a task. Co-pilots are an interesting example. During takeoff and landing—when they need intense cooperation—their brains synchronize. During the rest of the flight, not. In another study, after hearing a signal, paired subjects were supposed to silently count to 10 then simultaneously push a button. In repeated tests, as participants’ brains became more synched during counting, “the time interval between their button-presses was shorter” (p. 4). Other studies show this same convergence. Clearly, performance coordination improves.

What if we could use this to accelerate learning? Could we pair an expert and a novice on a skill and see the novice improve faster than through traditional methods? What about developing teams, especially where highly efficient fine motor precision and coordination is required? Surgery, for example.

Enjoying and Engaging with Other People

It seems when people need to work together, or enjoy collaborating, their brainwaves begin to synchronize. In a card game experiment, “believing” you’re part of the same team facilitated synching. Most of these studies don’t include participants’ subjective experience, but when they do there’s a clear correspondence between feelings and brain synchrony. For example, pairs who “felt” cooperative showed higher levels of neural synching while cooperating. Somehow, researchers got a class of 12 high school students to agree to inter-brain synchrony testing across a semester. Based on 11 class sessions, researchers could see synchrony associated with feelings of engagement, affinity, empathy and social closeness.

What We Believe Can Affect Whether Brains Synch

On the other hand, some people, and some situations, didn’t synch. Not all of the students in the classroom experiment synched with the whole group. People experiencing attachment anxiety or pain were less likely to connect in this way. As we would expect, people on the autism spectrum didn’t synchronize. Neither did people who were being competitive. People didn’t bond with a computer either. Even if they were paired with a human partner but seated at a computer and told they were interacting with the computer—when in reality they were interacting with each other—their brains didn’t synch. What they believed affected their neural activity.

Clearly, there’s a lot going on below the surface that we’re not consciously aware of. That’s not new. Psychologists and sociologists have known this for a long time. Their studies have included the subconscious, symbols, meaning and perception, for instance. Some of the “social neuroscientists” are weaving their physiological findings into what’s known behaviorally, helping to flesh out the complexity of who we are and how we experience the world together.

What About Implicit and Explicit Group Intent?

Another thing that interests me from the Valencia and Froese article is collective intent. They don’t really discuss it, but presumably they’re referring to the pairs of participants intending to achieve the tasks in the experiments. The classroom study involved a dozen people. In this natural setting, intent is more multifaceted. Learning the subject matter is the most explicit purpose, but there’s social learning going on too. And with 12 people, instead of two, there’s bound to be other intents, even if implicit.

What about even larger groups—100 or 1,000 people? If there was an explicit intent, would the same brain synching happen? We know from behavioral studies of group dynamics that the experience is different with 6-10 people, for instance, than with 2-3 or with 20-30. Yet there are times when it seems like a wave catches, enveloping even millions of people. That condition alone may be different than an intentionally designed test of 100 or 1,000 people, but it’s one of many questions that occur to me as I think about interdisciplinary investigation.

Would Brains Synch if People Work Together Remotely?

The logistics of testing this many people simultaneously would likely be difficult. Even with pairs, these are complicated, expensive studies to do given the necessary equipment, expertise and the need to shield subjects from other forms of electrical interference. The classroom study was done with cheaper, portable technology that’s now available to consumers. Signal quality is sacrificed, but it might work well enough for some tests.

I wonder if brain synching experiments could be done remotely? Would the brains of humans engaged in a shared task without being in the same room still synchronize? Neuroscientists don’t yet know “how” the synching happens, just that it does. Some think perceptual cues—like eye contact, facial expression and voice inflection, are necessary for brains to entrain. That suggests proximity is necessary. But then, we do have Zoom. Would that work? On the other hand, some of the findings involved what people “believe.” So, if we believe we’re working with others remotely, and we are, might brains still synch? Given COVID19 social distancing, it seems like an excellent time to test it and find out.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Throw a great big wrench into global society and the world slows down. With less human activity, wildlife is returning to cities and the air is cleaner. The earth is even vibrating less. What will we do with this slower pace?

Some are pushing to get the race pumped up again. And there are a lot of real problems people have to figure out how to deal with now and for the future since COVID-19 isn’t likely to be the last world-stopping event. But, rather than hurry past this time, why not use it to create new possibilities?

Photo by Christina Leimer

New ideas come out of a quieter time and pace. Stillness is the home of the imagination. Science and spiritual traditions agree. The Harvard Business Review encourages business leaders to play, to allow themselves and employees time to reflect to help possibilities emerge. Imagination, they say, is needed to shape the new environment. Shamans agree.

In American culture, it’s difficult to slow down and back off trying to fix a problem or come up with a solution. We believe it takes great effort and will. We have to “do” something. All the time. That’s a cultural bias that has far-reaching effects. Like so much human activity that the planet vibrates more.

In his book Courageous Dreaming, anthropologist, shaman and teacher Alberto Villoldo distinguishes between will and intent. Will is what we use “to try to force the world to conform to the way we think things should be, while intent is the mechanism by which we dream creatively and courageously.” (p. 67) “Will corrects and fixes things after they’ve manifested, but intent shapes things before they’re even born.” Both intent and will are needed—but at the right time.

With intent, we ask a broad question or hold a desire without specifying a particular tactic and then let the answer or condition unfold in its own time and its own way. Villoldo gives as an example the shamans he trained with in Peru. Their intent was to disseminate their teachings to the West. They didn’t develop a plan for how to do it, seek and evaluate potential messengers, or decide how they’d measure their success.

Instead, they took advantage of opportunities as they came. Villoldo was there doing research for his dissertation. He didn’t see himself as a potential shaman, spiritual tour guide or teacher. But the shamans saw him, and others, as a potential spokesman and nurtured it. They didn’t pressure, always leaving the decision—the will—and the way up to Villoldo.

When shamans say “dream the world into being” I take it as a more poetic way of saying let’s allow time for imagining and let our actions grow out of that receptive state. Lighten up, instead of bearing down. Can we?

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | As the World Changes

I’m starting to see articles speculating on what might change as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Some note that the changes following the 9/11 terrorist attack in NYC and the 2008 financial crash weren’t particularly positive. They didn’t change the trajectory the U.S. was already on. After 9/11, there was heightened monitoring of movement through airports, increased surveillance of citizens and long-term war. With the 2008 financial fallout, there were corporate bailouts with few financial controls and plenty of personal bankruptcies that tightened lending to individuals and made them renters instead of homeowners.

The same thing will happen with this pandemic if we act from the same basic underlying assumptions, or logics, of mainstream American culture.

Ways to Think About Cul

Source: Creative Commons

ture

There are many ways to describe culture and I’m going to take a few liberties with two models to make my point in this post.

A Management Science View of Culture

Emeritus MIT Management professor Edgar Schein’s model for organizational culture is fairly straightforward and can apply to societies. Schein describes 3 levels of culture based on the extent to which you can see it. The surface level is artifacts and behaviors—symbols like the flag, for example, the constitution, laws, policies, the ways we build cities, the transportation we use, and the processes for how we get things done.

Photo Courtesy of Creative Commons

The next level is espoused values—what we say we believe and the rules and norms we say we follow. It’s who we say we are, for example American grit or the land of opportunity, or compassionate and caring.

Below the surface is where things matter a lot—those deep, tacit beliefs drive our behavior and decision making. They’re so solid, so engrained, we rarely if ever question them. They give us certainty about the world and the assurance that we know how to navigate it. That profit motivates innovation, for example, or that individuals should pull themselves up by their own bootstraps, or family is the most important, or I have the right to defend myself.

A Shamanic View of Culture

Shamans too look at layers of human life—which includes culture. According to shaman Jon Rasmussen, there’s 4 layers—the literal, meaning the material world, including our bodies and the systems we create and products we build. That’s the surface. The psycho-spiritual/mind is something akin to the espoused beliefs, It’s how we process information, perceive and make meaning. While shamans, like organizational change managers, must work at all levels to create substantial, lasting change, it’s the two deepest levels where the most powerful work can be done.

Without change at the mythic and essential energy levels, the surface level changes won’t hold. The mythic is the images, stories and symbols that influence us usually without conscious recognition. It’s similar to Jung’s collective archetypes. We typically tap into it through ritual, art, music or dance. The essential energy layer is the soul. It’s where the blueprint lies for what we see on the other layers. Not only are the energetic and the mythic typically unquestioned and taken-for-granted, the energetic layer isn’t even part of secular mainstream Western culture. How we can access this layer for systems and culture change is a key question I have. But it’s a digression at the moment.

Intentional Change Takes Intentional Questioning

The point is, if we don’t unearth and intentionally question basic assumptions motivating our society and how we live, even if something changes after the pandemic, it’ll just be a different version of what we already have. There will be no fundamental change. The same, or worse, problems will recur at some point.

But, this kind of questioning creates huge anxiety and fear. Because we need the certainty of our taken-for-granted world to feel secure. That’s at least part of why presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders draws such heat. He’s pointing out the destructive parts of the way we’ve organized society and proposing new ways as a remedy. Those new ways rest on very different assumptions about how the world should be and our place in it.

So, what will change following the post-COVID19 pandemic? Surely, there will be tweaks. I think major change depends on whether we’re willing to honestly question what worked, what didn’t, why and related cultural assumptions while mitigating the fear and anxiety doing so causes. Then we can intentionally consider whether it’s time to re-make our world and how we might do it.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

In mainstream Western culture, if we give credence to dreams it’s usually for personal guidance, healing and insight. In many other cultures, especially shamanic ones, dreams can serve the collective as well. Neuroanthropologist Charles Laughlin (Communing with the Gods: Consciousness, Culture and the Dreaming Brain) says dreams play a role in producing social and cultural change. He goes on to say dreams “might be crucial in ameliorating the pernicious effects of materialism upon what is arguably an un-sane post-industrial society.” (p. 26).

Mudflats at Sunset Photo by Christina Leimer

Great! That’s what I think too. But how?

Here are a few examples of dreams as the impetus for large-scale change.

- Harriet Tubman’s dreams helped her free slaves through the Underground Railroad. They showed her ways to cross rivers and safe house locations she didn’t know before.

- Mahatma Ghandi’s idea for a general hunger strike as a form of nonviolent resistance to the British Raj in India came to him in a dream and it led to the independence movement.

- Frederick Kekule discovered the structure of benzene when he saw a snake biting its tail while he was dozing. That dream image led to understanding chemical bonding and organic chemistry.

- Robert Louis Stevenson dreamed part of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde while sick and sleeping. The book struck such a deep chord that it became a modern myth—human’s dual nature or the public and private self. It has carried along in Western culture as an idiom that refers to a person who’s both good and evil.

- Paul McCartney heard the melody to what became the song Yesterday so clearly in a dream that he thought someone must have recorded it and he was just remembering it from somewhere in waking life.Yesterday became one the most popular songs of the 20th Century.

- Larry Page received the basis for what became the Google search engine in a dream, though he had to work out the specifics in waking life. It seems to be common that dreams point the direction or give clues then leave the details to the dreamer or community. According to anthropologist and shaman Michael Harner (The Way of the Shaman), dreams can be literal though, especially visionary dreams, and require no interpretation or extending. They may be prophetic.

There are usually dream specialists of some sort in cultures that recognize dreams for the collective. Shamans are an example. Dream specialists develop expertise and guide people to share, understand and even interact with dreams. Sometimes the dream specialists interact with dreams on others’ behalf or on behalf of their community. But, in these cultures, most people are socialized to the importance of dreams. They grow up talking about their dreams and their meaning. Physical places and ways to share dreams with others in wake life exist too. It’s not about saying, wow, that’s bizarre! The sharing is to help people understand the dream’s meaning and co-create it or validate it, especially when the dream is a “visionary” dream.

Dream-teacher, shaman and author Robert Moss teaches people what he calls “active dreaming.” It’s not dream interpretation, analysis or decoding—he wants to make clear. Active dreaming is a journey “to reclaim ways of seeing and knowing and healing that were known to our early ancestors. … It is a way of remembering and embodying what the soul knows about essential things.” (Active Dreaming: Journeying Beyond Self-Limitation to a Life of Wild Freedom, p. 3)

Moss believes Western culture is in dire need of re-connecting to our dreams and the deeper levels of knowledge and existence dreams provide us. That’s why he teaches people to become dream-teachers. He also teaches co-dreaming, or creating a group vision and jointly dreaming it into existence.

Some of these teachers-in-training are interested in how dreams can be used to change society. In one of his sessions, they suggested curing disease, bringing dreamwork into healthcare, healing the oceans and fish, electing a woman president of the U.S., healing the rage and violence that brings war and terrorism, world peace and creating a dreaming society. (p. 204)

Guess I’m not the only one searching for ways that alternative states of consciousness can help us create a more humane and nourishing world for people, planet and all life.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist