by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

In an unusual new study, researchers asked sleeping lucid dreamers to solve simple math problems. Some did. When they asked these dreaming people yes/no questions, some answered–using a raised eyebrow or a smile. The researchers call this 2-way communication “interactive dreaming.” Its potential could be wide-ranging.

Source: Dreamtime.com

The experiment, published in Current Biology in February 2021, involved 20 scientists on four independent research teams in four countries: the U.S., Germany, France and the Netherlands. In total, they tested 36 dreamers, during 57 sessions, making 158 communication attempts. The dreamers were people with little or no experience with lucid dreaming, experienced lucid dreamers, and one lucid dreamer with narcolepsy. Dream sessions happened during night time sleep as well as daytime naps.

Training the Brain for Lucid Dreaming

Before the experiment, they taught the inexperienced dreamers how to lucid dream. Also, they practiced answering questions with the pre-arranged facial expressions and eye movements but were not told what questions would be asked.

Three of the four teams used different methods to question the dreamers. One asked math questions using Morse code and multi-colored lights. Two teams verbally asked the math questions. The other team verbally asked yes/no questions. In all sessions, dreamers were to move their eyes in a pre-determined way to signal when they were lucid (aware that they were dreaming). However, that happened in only 26% of the sessions. Also, some wake up when being spoken to. Consequently, they based their final results on only the cases where dreamers signaled and the signal was verified by the brain wave data being recorded.

For example, after one inexperienced dreamer moved his eyes to show he was lucid, researchers asked, what is 8 minus 6. Within 3 seconds, “he responded with 2 left-right eye movements (LRLR) to signal the correct answer.” The same problem was asked again. Again, he answered correctly.

In another case. The narcoleptic lucid dreamer was asked yes/no questions. He answered correctly using a smile for no and a raised eyebrow for yes. He answered 4 of the 5 questions, 2 correctly and 2 answers were ambiguous. In his waking report of the session, he repeated the questions the experimenter had asked.

In a third case, an experienced lucid dreamer was “presented visual stimuli consisting of alternating colors and a corresponding Morse-coded math problem 4 minus 0.” He answered with the correct number of eye movements, but in his waking post-dream description said he had heard the question as 4+0. He also reported knowing the flashing lights were math problems, but sometimes they were too fast to decode.

Interactive Dreaming Proof of Concept

Overall, there were 29 correct responses from 6 different individuals—at least one from each team. Also, during day and night sleep. The researchers call the results “proof of concept of two-way communication during sleep.” Most people couldn’t do it. But clearly, it can be done.

Receiving and answering questions engages high-level cognitive skills. Skills that were previously thought impossible while sleeping. Lucid dreamers were able to remember instructions given during waking and apply them while sleeping. They were able to calculate, to answer the math questions and were able to access memories of their waking life to correctly answer the yes/no questions. So, aside from deepening sleep and dreaming research if dreamers can offer real-time information from the dream state, what do these experimenters think the potential, someday uses are?

Potential Uses of Interactive Dreaming

Interactive dreaming could be used to solve problems and enhance creativity, they speculate, and to learn new facts and skills. Previous studies suggest dreaming about athletic or musical ability when it’s being developed in wake life can enhance performance. In my own experience, dreams helped me solve problems. Usually that happened by simulating scenarios in the dream and seeing how they played out or rehearsing different responses to complex social situations.

The experimenters say artists and writers might gain inspiration from sleep communication. As I wrote in another post, artists, writers, scientists and other creative people have long found solutions and new directions through dreams and daydreams.

Healing Using Dreams

They suggest interactive dreaming could be used to reduce effects of emotional trauma and find novel ways to promote health and well-being. At the end of January, I listened to an Institute of Noetic Sciences webinar announcing a study they plan to do to see whether healing intention in a lucid dream can actually heal people in waking life. I’ve experienced this, and even experienced actual healing “in” dreams.

As a kid and until about my mid-twenties, when I was in pain or emotionally upset, I slept. For many, many hours. When I woke up, I was pain-free or in a re-balanced mood. I usually didn’t set an intention for healing, and I don’t recall remembering what happened in most of the dreams, so they weren’t lucid. But they show me that some kinds of healing can happen during the dreaming state.

They say combining the “creative advantages of dreaming with the logical advantages of waking, cues may be devised to influence dream content” for any of these purposes. Understanding the dream process as we’re dreaming may even “open up new ways to address fundamental questions about consciousness.”

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

If there’s a field that screams logic to me, it’s math. So I was surprised to learn that intuition and the subconscious mind propelled many of the greatest mathematicians to their discoveries.

Source: Shutterstock

In his book, The Psychology of Invention in the Mathematical Field (1944), French mathematician Jacques Hadamard (1865-1963) says sudden flashes of insight provide breakthroughs. Also, that some mathematicians are mostly logical in their thinking, while others are mostly intuitive.

3 Processes of the Inventive Mind

Hadamard came to this conclusion by observing his own mental workings, reports from other highly accomplished mathematicians, psychologists’ investigations and a famous lecture French polymath Henri Poincaré (1854-1912) gave at Société de Psychologie in Paris in 1937. In that address, Poincaré shared his creative breakthrough experiences. He talked about how his mind works and generalized the process into three stages: 1) preparation, 2) incubation, and 3) illumination. Hadamard agrees, but adds verifying and “precising” after illumination.

Not all inventive minds work alike, Hadamard says. But there’s a basic process, with some variations. It doesn’t just apply to mathematical geniuses either. It’s common in other sciences, literature, arts and technology. It even shows up in ordinary life for most of us, if in more mundane ways.

Preparing the Subconscious to Invent

The first stage, preparation, begins with intense, conscious work. Whatever the question or problem to be solved, the scientist or seeker examines theories and facts, turns it over and over in their mind, asks “what if” and tries to find an answer or solution. There may be repeated failures. It’s conscious, deliberate, informed mental work. Eventually, the person gets stuck or feels like there is no answer.

Incubating Inventive Ideas & Solutions

At that point, they put the question and the struggle out of their mind and go do something completely different. Take a walk, or a vacation, or go to a party. Maybe take up a different question. Whatever. But nothing to do with the problem they’re stuck on. This is the incubation stage. It seems like the work has stopped. Maybe even died. But Hadamard says the conscious effort has triggered the unconscious to take action and shaped its direction. There’s something going on in our depths. We’re just not aware of it. Incubation may last a day, a week, months or much longer.

Eureka! Illumination Shows the Answer

Incubation breaks when insight hits. That’s the third stage, illumination. The insight is brief, sudden and immediately certain. Hadamard experienced this when a noise woke him abruptly from a dream during an emotionally intense time in his life. The moment he woke, the solution appeared. He described the experience as unforgettable and the solution was in a different direction than any he’d tried before.

In his lecture, Poincaré said he spent time trying to prove that fuchsian functions couldn’t exist. Then, during a sleepless night bolstered by black coffee, he asked what properties these must have if they exist. Ideas flooded his mind. He developed one class of these functions then got stuck. So he put the math aside and went traveling. As he stepped onto a bus while talking with a friend, an idea about fuchsian groups came to him in a flash, momentary and certain. It was so fleeting that the conversation never faltered. He intended to verify the insight when he returned home.

Invention & Discovery Require the Whole Mind

How does that insight emerge? Hadamard considers freshness, the idea that the mind gets a break and is then able to re-start. He also considers the “forgetting hypothesis.” That the mind has time to forget all of its wrong turns and frustration and can start over. He rejects both ideas.

Instead, Hadamard and Poincaré think the conscious and unconscious mind is working in tandem. Invention and discovery occur by combining ideas. There are many combinations—most of them uninteresting or useless for the problem at hand— that must be sorted. The sorting process takes place in the unconscious. After it’s been given direction, or educated—as Poincaré called it, by the conscious mind’s work.

The Unconscious Mind Taps Will & Emotion

The unconscious includes many layers, some that are very deep. Much of its processing we’ll never be aware of, and so never know all of the combinations it tossed around. Those that leap into the conscious mind, they say, are the combinations or ideas that profoundly affect our emotional sensibility—in the case of mathematicians, beauty, harmony—and therefore most likely to be useful. Hadamard says an affective element is an essential part of every discovery or invention. He calls “the will of finding” an affect or esthetic.

The Conscious Mind Verifies

After illumination, or inspiration, the conscious mind goes to work again. It must verify in some way that the insight is correct, despite the immediate sense of certainty. Usually this involves a working out of the solution, drawing out its details and methods and making it more precise. In the case of writing or art, this may mean finding just the right word or image or fleshing out the insight.

Intuitive Invention Process Varies

Some part of the process can vary between individuals. For instance, for Hermann von Hemholtz, a physicist and physician of Hadamard’s time, “happy ideas”, which is what he called illumination, don’t happen when the mind is fatigued. For him, there was a very precise time that his mind needed to refresh. Afterward, these happy ideas may show up. The process can even vary in some ways for the same person under different circumstances or at different times.

What is Hadamard’s example of how this works with even mundane things? Ever tried to recall a name or place and you just can’t? After you stop trying, forget about it and go on with your day, that deeper part of you coughs up the answer—maybe when you’re stepping onto a bus.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Source: Deposit Photos

An intriguing description of how intuition works comes from Ingo Swann’s explanation of ESP. Swann, along with Stanford physicist Harold Puthoff, developed the process for remote viewing that the U.S. military used. Swann, a remote viewer himself, did the teaching. In his book, Everybody’s Guide to Natural ESP, Swann says anyone can do remote viewing. Essentially it involves nonconscious information rising to consciousness. Here’s the gist of how he thought it works.

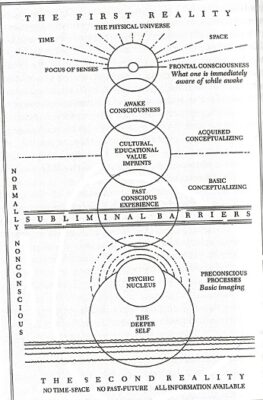

Subliminal Barrier Filters Information

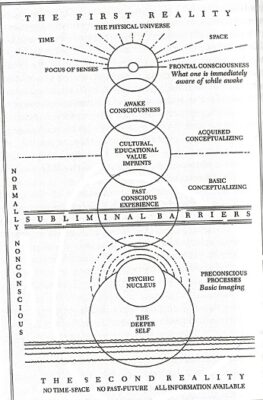

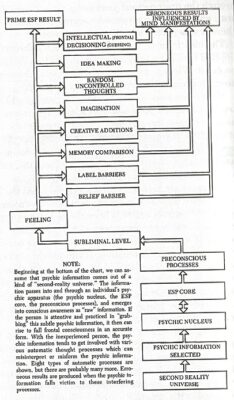

Our “deeper self,” our subconscious, transcendent self, soul, or any variety of names for it, is connected to the energetic quantum information world underlying the physical universe—the “second reality” notation at the base of the diagram below from Swann’s book. That’s where the intuitive information comes from. So that we’re not flooded and overwhelmed, Swann says a subliminal barrier allows only select information to make it to our conscious, waking mind. Without that barrier, it would be like listening to 1,000 radio channels simultaneously. Usually we receive the information that’s most important to us.

Like the quantum world itself, which physicists are still trying to understand, intuition works by its own logic and processes. Those are represented in the diagram by the overlapping circles in the nonconscious space below the subliminal barrier. The deeper self’s qualities must operate similar to those of quantum reality, which facilitates the connection. Neither intuition nor the quantum world seems to be affected by time, space or the resistance of matter.

What’s Going On Below the Mind’s Surface?

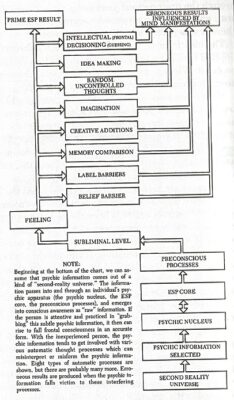

So, what’s going on below the subliminal barrier? What are those preconscious processes? It’s murky. Nonconscious stimuli enter idea and creativity generating processes that interact with memory to take on a form that can be recognized by logic and analysis when it reaches conscious awareness. This subjective process cannot be willfully controlled. With practice, it can be recognized though and conducive environments can be set up to facilitate it. Artists and other creative professionals often use rituals, a favorite place, or some personalized means to bring on the muse. Swann thought ESP uses the same channels and similar processes.

Unlocking Natural Talents & Learning Discernment

Focusing attention and training awakens our waking consciousness to the deeper self’s workings. Even so, the nonconscious information we access can be diverted or misinterpreted by conceptualizing filters on its way to full frontal consciousness (shown in the upper portion of the diagram).

That’s what training helps with. In his book about working as a remote viewer for the military, Lyn Buchanan says Swann’s method doesn’t “teach someone to be psychic.” It “teaches them to get rid of all those blocks that prevent them from using the natural and hidden talents they already have. For most people, that is a surprising amount.” (p. 32). Like any talent though, some people are more naturally able to access subliminal information and bring it accurately to consciousness than others.

This diagram, also from Swann’s book, shows some of our basic and acquired conceptualizing filters that can keep our deeper self’s messages from getting to waking consciousness fully and accurately. The conscious mind uses these frameworks and strategies to process information. They may work well with information our normal sensory system brings in. But intuitive information is likely to be grasped whole; those sudden insights that don’t need interpretation. Their meaning is clear on arrival. If the info gets snared by these filters instead of reaching waking consciousness raw, it may come out partial or wrong. It’s possible though, if the conscious filters align with the intuitive content, the conscious message could be reasonably accurate.

For most of us, nonconscious information appears sporadically and spontaneously, often in bodily or emotional form or in dreams or daydreams. The sense that someone we love is in danger is a good example. We may not know the specifics, just the visceral sense or physical discomfort and who it’s associated with. How the deeper self initiates that spontaneous, non-conscious awareness that shoots directly to the surface remains a mystery, one even Swann didn’t understand.

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Researching Consciousness for Social Change

Source: Pixabay

I hear so many quotes attributed to Albert Einstein, it made me wonder what he really did say. So, I went searching. It’s difficult to tell from quotes what Einstein thought intuition is or where it comes from, but intuition, imagination and insight were definitely part of his ways of knowing and discovering. Here’s some of what he said about it (from The Expanded Quotable Einstein, 2000):

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

“I believe in intuition and inspiration…At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.”

“I believe in intuition and inspiration…At times I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason.”

“My intuition was not strong enough in the field of mathematics to differentiate clearly the fundamentally important…from the rest of the more or less desirable erudition. Also, my interest in the study of nature was no doubt stronger… In this field I soon learned to sniff out that which might lead to fundamentals and to turn aside…from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind and divert from the essentials.”

“My intuition was not strong enough in the field of mathematics to differentiate clearly the fundamentally important…from the rest of the more or less desirable erudition. Also, my interest in the study of nature was no doubt stronger… In this field I soon learned to sniff out that which might lead to fundamentals and to turn aside…from the multitude of things that clutter up the mind and divert from the essentials.”

“The truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a way almost diametrically opposed to induction. The intuitive grasp of the essentials of a large complex of facts leads the scientist to the postulation of a hypothetical basic law, or several such laws. From these laws, he derives his conclusions…which can then be compared to experience. Basic laws (axioms) and conclusions together form what is called a “theory.” Every expert knows that the greatest advances in natural science…originated in this manner, and that their basis has this hypothetical character.”

“The truly great advances in our understanding of nature originated in a way almost diametrically opposed to induction. The intuitive grasp of the essentials of a large complex of facts leads the scientist to the postulation of a hypothetical basic law, or several such laws. From these laws, he derives his conclusions…which can then be compared to experience. Basic laws (axioms) and conclusions together form what is called a “theory.” Every expert knows that the greatest advances in natural science…originated in this manner, and that their basis has this hypothetical character.”

“All great achievements of science must start from intuitive knowledge, namely, in axioms, from which deductions are then made…Intuition is the necessary condition for the discovery of such axioms.”

“All great achievements of science must start from intuitive knowledge, namely, in axioms, from which deductions are then made…Intuition is the necessary condition for the discovery of such axioms.”

“I very rarely think in words at all. A thought comes, and I may try to express it in words afterwards.”

“I very rarely think in words at all. A thought comes, and I may try to express it in words afterwards.”

“I was sitting in the patent office in Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me: if a person falls freely, he won’t feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.”

“I was sitting in the patent office in Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me: if a person falls freely, he won’t feel his own weight. I was startled. This simple thought made a deep impression on me. It impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.”

“I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without the use of signs (words), and, furthermore, largely unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts that is already sufficiently fixed within us…The development of the world of thinking is in effect a continual flight from wonder.”

“I have no doubt that our thinking goes on for the most part without the use of signs (words), and, furthermore, largely unconsciously. For how, otherwise, should it happen that sometimes we “wonder” quite spontaneously about some experience? This “wondering” appears to occur when an experience comes into conflict with a world of concepts that is already sufficiently fixed within us…The development of the world of thinking is in effect a continual flight from wonder.”

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist

by Christina Leimer | Society/Culture

Source: Getty Images

In our COVID-19 era, we’re getting closer to nature.

Kayaking, biking, hiking and other outdoor activities are booming. Some schools are teaching in-person classes outside. So many high school and would-be college students taking a gap year want to participate in semester-long nature-based programs that these schools are flooded with applicants. The number of nature-based pre-schools has been growing rapidly, even before COVID hit. Even some doctors are prescribing walks in nature for health and well-being.

Will this heightened amount of outdoor activity have long-term effects for individuals, society and the planet? If so, what might those be?

Based on studies using the Connectedness to Nature Scale, people who score higher are better able to reflect on life problems, take others’ perspectives, feel a sense of belonging and are typically more open to experience. A meta-analysis of research about the natural world’s effects on child development and learning finds that learning in a natural setting improves concentration, cooperativeness, engagement, self-discipline and physical activity and decreases stress.

In our stressful, complex, interdependent world, where we need to understand and cooperate with each other more and mitigate negative human effects on the environment, the benefits of nature connectedness and learning in nature are invaluable. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, some nature pre-schools are intentionally multicultural to ensure all children, families and communities reap the rewards.

The Director of the Sierra Club’s Outdoors for All campaign says this time period is a once in a generation opportunity to re-imagine schools and connect kids to the natural world. In addition to the longstanding environmental and conservation groups, many youth groups have formed to protect the natural environment and help reverse climate change.

But in the COVID-era, adults are benefiting too. Will we keep our closeness to nature going post-COVID?

Subscribe

Christina Leimer, aka The Intuitive Sociologist